This excerpt from Rooted in the Earth, “Chapter 9 Women and Gardening: A Patch of Her Own,” by Dianne D. Glave was my first introduction to my new favorite artist Clementine Hunter. Since reading Dianne’s book back in December I have been endlessly researching who Clementine was & what her life was like. I don’t have all the answers, but much of the documented information I found led me to ask more questions. Sometimes, the sources I found sadly affirmed the reason why I started this publication.

According to the melrose plantation website, where Clementine spent most of her life, Clementine originally worked in the fields just as her enslaved grandparents had done under a new system named sharecropping.

“Clementine began as a field hand at Melrose when she was twelve years old. Originally born at Hidden Hill Plantation in 1887, her family moved to Melrose as sharecroppers for the Henry family. Later she became a house keeper, but it was while she was a cook that she found some discarded paints left behind by an artist at Melrose. Those discarded paints changed her life. Clementine Hunter’s paintings continue to touch those who view and admire her work each day.”

Upon my first reading, this excerpt from the plantation website seems to stick closely to the facts. However, everyone has a mission & the melrose plantation website’s explanation of how Clementine Hunter came to be a great artist is no different. The syntax of the words leads the viewer to believe if it had not been for the various places, the house and kitchen, on the plantation then Clementine’s life would have never been changed. Those discarded paints changed her life. While I’m sure for Clementine having the means to document her rich inner world was life-changing, especially because she couldn’t read or write, there are more life-changing things that could have happened to her. The system of sharecropping, like slavery, did not bestow gifts upon Black Folks. Yet, the melrose plantation continues to feed the narrative that the discarded trash offered to those who labored for next to nothing was worth more than gold. The melrose plantation website goes on to say that…

“Clementine was a self-taught, primitive artist. She never completed any formal education and did not learn to read or write. She expressed herself, told her story, through paint. Her unique African-American perspective, considered "insider art," tells stories that historians overlooked while documenting plantation life. Plantations are far more than the big house and the crop produced. Clementine captured the community of workers, the life of the "gears" that make plantations successful and prosperous.”

The first line alone is evidence of the lazy language the art world, and society at large, continue to use to engage with the South & Black Southerners. An emphasis on self-taught, folk, vernacular, & primitive are simply labels people use as a border of separation that requires no true understanding of Southerners’ complexity. Primitive, in its noun form, has many definitions recorded by the Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

Definitions 2b-3b are the meanings that hold true for what the melrose plantation was intentionally desiring to communicate about Clementine. The plantation wanted to communicate that while these discarded paints changed her life, the work she produced was that of an unsophisticated person and a member of a primitive people. Not only was Clementine considered primitive to the owners of the plantation, but so were the other sharecroppers on the land. The connotations of simple & unsophisticated followed Clementine throughout her artistic career. There was a constant tension in what embodied knowledge & memories Clementine knew, and how others wanted her to express it to garner more refined respect.

Additionally, the plantation’s language choice of the “community of workers” is reminiscent of the “community of cooperation” Joseph Emory Davis (eldest brother to the president of the confederacy) called his plantation. Despite the fact that Clementine lived on & documented a plantation as a sharecropper and Davis claimed to own 350 slaves, the choice to push community to the forefront is clear. While it is true that these Black Folk found ways to be in community the plantation’s propaganda makes it seem like community was more than enough to make up for what was taken from them. Slavery & sharecropping are two sides of the same coin. The so-called “gears” of the plantation that made it “successful and prosperous” were human beings. Black folk are people who are treated as pieces of machinery, grinding themselves down in an attempt to stay above it, & never receiving proper care. This is not a success, & Clementine’s life did not vary much from this image even as her artistic career took off. There is no time to rest when you are a person, being treated like a gear, that sounds like a ticking clock set against your lifetime.

This is why after 1918, when one of the owners of melrose “not only maintained the agricultural empire but also created a haven for artists, craftsmen, and authors. Melrose became a retreat for visiting artists and a center for creativity” it raises many points of tension. Turning a plantation that was made successful through the forced labor instituted by slavery and then the little choice freedmen had to become sharecroppers is the rotten nostalgia of the South. It’s the alluring charm of horse-drawn carriages on cobblestone roads in Charleston, South Carolina, and the whimsical Spanish moss hanging from ancient trees in Savannah, Georgia. One thing about cobblestone roads is you will trip on a misplaced stone & from trying to catch the moss you will release mites, ticks, & a host of other vile beings caught in its memory web. Turning a plantation into a site of leisure & rest for temporary visiting artists while being made possible by sharecropping is also vile work.

The melrose plantation site stated that it would go on to host “many well-known writers and artists of the early 20th century. This period of arts revival is now known as the “Southern Renaissance.” Lyle Saxon, who acted as a catalyst for the Melrose artist retreat, wrote his best known novel Children of Strangers, which portrays the Cane River region, on-site. Melrose and Cammie Henry hosted many of the prominent figures of the Southern Renaissance including William Faulkner, Rachel Field, Ada Jack Carver, Roark Bradford, and Alberta Kinsey.”

I wonder what it would have been like for Clementine to have to continue working all day, gather discarded materials by privileged artists whom she worked in service to, and paint all hours into the night. I imagine the heart-wrenching feeling of watching artists come to Cane River & be expected to do nothing but create. This seems to me to be representative of the latter definition 2b(2)... naivete: a state of blind faith in the land and not knowing how to read it…see through it.

François Mignon supports this claim by stating that visiting artists were exposed to “ a certain amount of quiet & relaxation that rather inspires them.” Though Migon was a firm supporter, & in some ways a patron of Clementine’s work, he fails to see that the people labeled gears were art themselves. Black folks being art, embodying & gathering beauty to make an assemblage was not attributed to melrose. Any other notion of Clementine’s artistic gifts being tied to the system of sharecropping participates in the same lineage as Phillis Wheatly…a desperate attempt to mark the experiment of white supremacy beneficial regardless of expectations to the rule.

Clementine is direct, her paintbrush is exposed spanish moss breaking open the enchanting web of the South. This video clip (2:52-4:10) exemplifies the discomfort many people face in interacting with the springing people of the South. Moreover, this clip embodies the central tension this publication is rooted in…the fact that there is no critical language to deeply discuss & engage with the work (& artist who produces it) because black subjectivity is rooted in the vernacular. The problem does not lie in the word vernacular alone. The problem lies in the bias, prejudice, & disregard that occurs in one’s brain when the term is used. No one, has ever taken the time to understand those who collect, arrange, & make beauty from discarded things in discarded regions of the world.

So instead we are left with language like the one we see in this clip. Clementine is re-introduced to us as a primitive artist because she can’t be classical because she doesn’t follow the form 🙄. Moreover, Clementine is not classically trained she is self-taught. We are forced to watch this awkward interaction of the interviewer asking Clemtine to explore her marks. The interviewer is excited to hear each answer. But not in a way that seems genuine, but almost like a child who has drawn a picture of you & you must feign excitement despite the fact that you see absolutely no resemblance. My favorite part of the uncomfortable interaction is when Clementine asks the interviewer, “you ain’t never washed on that.” I recognize the tone of voice all too well. It’s Clementine’s way of asserting her knowledge of a specific way of life that doesn’t need to be externally validated. In other words, it is Clemtine’s way of saying hush up, I already done told you what my marks are.

There is a level of respect that must be honored in terms of how one expresses themselves verbally. So often, grammar is enforced as a hierarchical system that people use to police other’s expressions of self. Early in the interview, the interviewer communicates to the viewer Clementine’s process using the word stroke. However, when the interviewer introduces Clementine’s work she says, “her marks as she calls them.” This choice of language undercuts Clementine’s agency to assert her process in a way that feels authentic to her. It’s the same reason why so many folks whose mother tongue is English are quick to correct Palestinians who call their loved ones whose lives were taken, martyrs. There is no correction for what the mind feels is the proper word to call home. Palestinians say martyrs so I say martyrs; Clementine calls them marks, so I call them marks. What policing language really boils down to, is an unwillingness to understand a people, culture, & or region that emotes differently from you. Your standard vocabulary knowledge has limits to its expression & everyone’s standard is different.

On page 86 of Art in My Mind, bell hooks emphasizes the tendency that people tend to have when engaging with art from the South. hooks says that people tend to “reduce it to something simple about the South and how the folks do creative shit with trash.”1 Southerners’ gathered lives have been simplified into one-dimensional childlike narratives or activities. Yet, Black Southernes have used “vernacular art” such as quilting to tell their own stories and be their own subjects for generations. Furthermore, Black Southern’s narratives and choice(s) of mediums are far from simple and enable a vibrant interior life to become materialized. Clementine’s vernacular art was no different because of the fact that she used a variety of found materials. According to the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA)…

“Hunter painted at night, after working all day in the plantation house. She used whatever surfaces she could find, drawing and painting on canvas, wood, gourds, paper, snuff boxes, wine bottles, iron pots, cutting boards, and plastic milk jugs.”

This is reminiscent of the late Toni Morrison who also put her first artistic work into the world in her late 40s/early 50s. Except Toni used to get up at 4 a.m. with the sun to write before her two sons rose from their restful sleep. Furthermore, both Toni & Clementine worked intimately with memory.

Clementine & Toni used “emotional memory” to document the original places they had been. Although Toni also stated that she had a “wish to extend, fill in, & complement.” Whereas Clementine, as a sharecropper & granddaughter of a formerly enslaved couple, strictly documented the original place of the Deep South she was raised on. For every official record that regulated Black people to numbers, Clementine provided a rogue “route back to our original place” through her paintings.

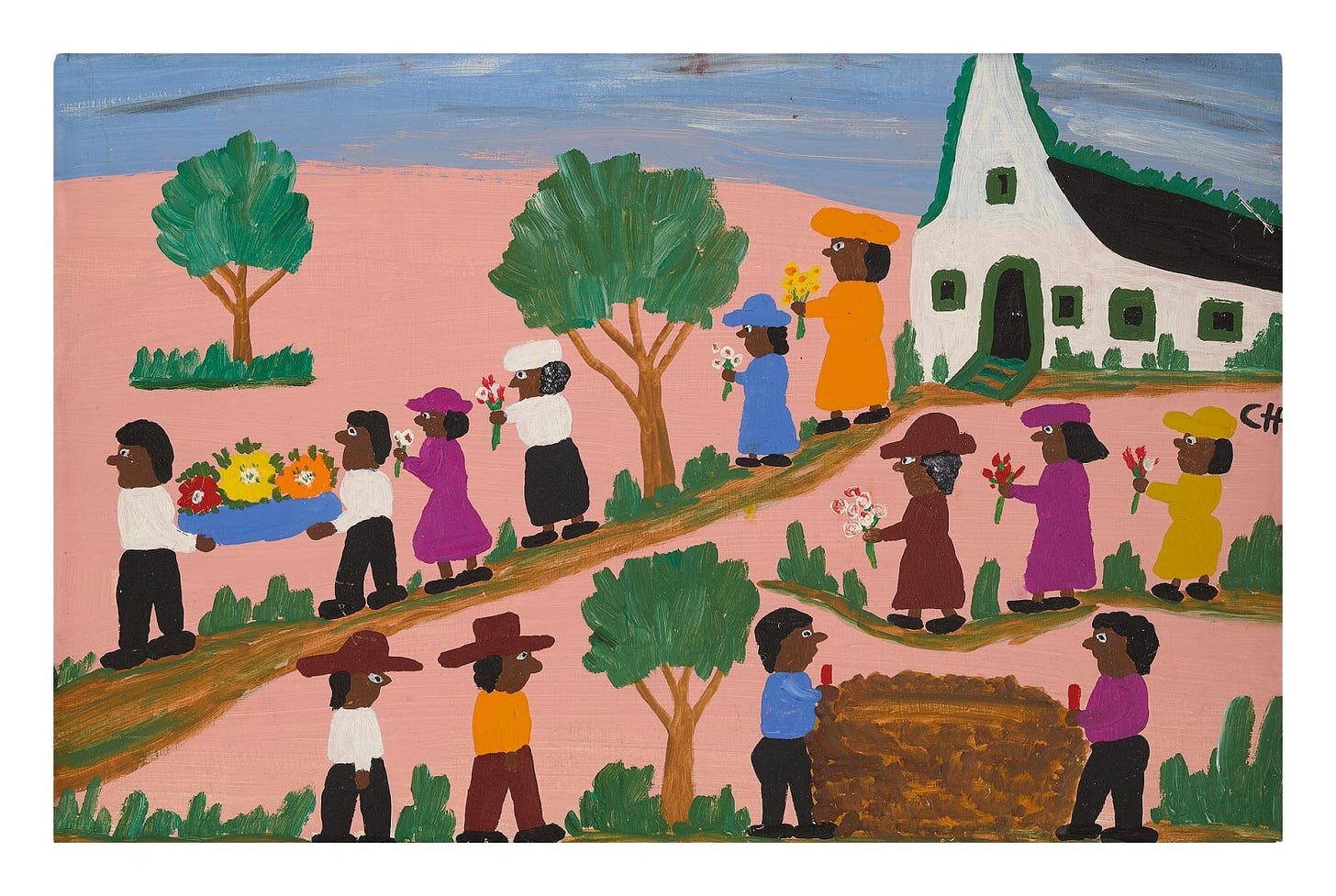

The NMWA stated that from Clemntine’s process of “working from memory, Hunter recorded everyday life in and around the plantation, from work in the cotton fields to baptisms and funerals.” Clementine participated in memory work & that is a skill that deserved to have been highlighted by the interviewer. Rather than asking Clementine if she “swirled them,” the clothes in the container, she deserved to be asked about the “remembering” from her mind to the canvas. I see Clementine remembering within the vibrant colors & swelling stark strokes of paint to create movement. I see how Clementine made an assemblage of her life and artistic work. I wish the language of assemblage had been used in relation to her marks earlier. However, Clementine marked her time earthside remembering the feelings of places, people, & language that honored the original place from which she descended. Assemblage provides a language for those whose artful lives are handled improperly due to an unwillingness to call a mark a mark. Assemblage will continue to provide the language to describe the subjectivity that Clementine was always in possession of.

Always.

Always.

Always.

Art on My Mind by bell hooks