Zone Zero: Black Womxn Assemblaging an Artful Life is the title of my senior thesis that I successfully defended and passed with high honors in May of 2023. Since graduating, I have given myself ample free time to truly process graduating college in three years, in a pandemic, and what a successful life looks like (& more importantly feels like) for myself. My senior thesis abstract is as follows:

“Have you ever had the experience of watching yourself being watched? Maybe you changed how you walked or ate your food as a result. This behavior demonstrated the internalization of surveillance. The purpose of my project is to explore this process in an attempt to learn how to break the habit of self-surveillance. Specifically, Black women whose movements are surveilled by both the inner and public eye. How can you move more freely in a world blinded by light as a dark human being? This thesis pivots to conjure how Black womxn can live in a world without choosing select spaces where they can express subjectivity. The goal is not to develop a toolkit to help Black womxn subvert the system that continuously rejects their humanity. Instead, the goal is to create sovereignty in all places, free of restrictions, and eradicate self-discipline (and thus state surveillance) as a whole. As a result, this exploratory thesis will utilize a Black Feminist framework to deepen the analysis of visual art interventions and offer holistic takeaways to society.”

Assemblage is a term that I defined in my senior thesis to describe the work Black Womxn do to create bountiful and beautiful lives for ourselves & on our own terms. Assemblage is rooted in waywardness, debunking fugitivity, and with an emphasis on the vernacular. Spelling woman as womxn is a choice I made while writing the thesis to make space for the complexity of gender that can be denied by the academy.

One of the three visual artists whose world I explored was Carrie Mae Weems. In Art on My Mind bell hooks has a conversation with Weems about her art practice. hooks admits to Weems how shocked she is that “no one writes about the place of vernacular culture in your work, in the images” (hooks, p. 89). Within visual art there has historically been a separation of vernacular, sometimes called folk/craft art, from high culture art. The real distinction between the two is perhaps access too formal training (like a MFA), spaces where the visual art is accessed (museums & galleries), and perhaps the most overlooked one… assumptions about where the artist calls home.

Within my thesis, I was doing a visual analysis on I Looked and Looked and Failed to See What So Terrified You from Weems’ Louisiana Project Series. However, the Louisiana Project was not Weems’ first exploration of the South. Weems did a series entitled The Sea Island Seris from 1991-1992. hooks and Weems discuss the piece entitled The Mattress Springs in this specific interview. When exploring The Mattress Springs, hooks emphasizes the tendency that people tend to resort to when looking at art from the South. hooks makes the claim that people have a tendency to “reduce it to something simple about the South and how the folks do creative shit with trash” (hooks, p. 86). An assemblage, & the found materials used to make the assemblage, certify the assumption society & art engagers have with artists from the South. The assumption is that they come from trash, are trash, & create pieces of trash, and call it art. Hooks continues to give high regards to Weems by writing that Weems and other image makers “who are engaged in ongoing processes of decolonization and reinvention of the self, whose work cannot be understood deeply because we lack a critical language to talk about contemporary radical black subjectivity” (hooks, p. 91).

My thesis argues that the reason we don’t have a critical language to discuss contemporary black subjectivity is because the language is rooted in the vernacular. Without a deep understanding of one’s subjectivity, it becomes difficult to recognize oneself as a true subject or person. An easier way to understand subjectivity is that it is a term used to describe the difference between what conditions enable some people to feel that they are the main characters in their own lives. Whereas when subjectivity is not understood or realized, the lack of language to talk about it can leave others feeling like supporting roles or simply props in a film they didn’t choose to exist within.

The many vernacular aspects of an artful life are what sustains the planet and close-knit communities. The vernacular elements of life, which are deeply ritualist art-making skills, are sustainable to one’s culture and support one’s physical well-being in a crumbling world. Yet, like vernacular art and assemblage pieces, no one cares about how Black people gather found/natural beauty to make a life. Within the exhibition catalog Southern Accent: Seeking the American South in Contemporary Art, Brendan Greaves truthfully excavates the root of the true sentiment of Southern Vernacular. In Greaves’ essay, “Humming This Song Trying to Remember the Way Another One Goes: Intermedia Conversations in a Southern Vernacular”, he writes that the use of an arsenal of clumsily imprecise terms like ‘outsider’, ‘self-taught,’ ‘folk,’ and ‘visionary’- language that unlike the array of genres identified with southern music, describes the viewer’s assumptions about the artist’s identity more than the nature of the art itself” (p. 139). While Greaves was discussing the Southern region of the U.S., the South at large can be considered any place not in the West that fosters fear of otherness creating amazing art. I argue that this oversight, the oversight of getting to know the art intimately, produces a vacuum in ways Black Womxn give credit to the vernacular ways they gather beauty to stitch a life together.

The word choice, gather is important to note and brings to mind many associations that I have gathered & collected in my own mind. I’m reminded of Toni Morrison's writing in her 1998 novel Beloved. Morrison writes Sixo’s definition of love as “she is a friend of mind. She gather me, man. The pieces I am, she gather them & give them back to me in all the right order.” My mind recalls images and tales of Black womxn gathering branches and other limbs of squatted & standing greenery to make brooms to cleanse their dwelling space & front porches. I too, am reminded of Black women gathering scraps of cloth & no good hand-me-downs to make quilts passed down for generations. I can recall Black women in personal gardens gathering fresh crops to make themselves a good meal. Or the gathering of red clay to make vessels & proclaim them your own in writing in the case of Dave Drake the potter, man, & human. Lastly, a sweet image of Edna Lewis surrounded by bursting sun flowerings, holding a basket of gether tomatoes. The ritualistic process of gathering and collecting for both utility and beauty is the most important thing towards black subjectivity and it is vernacular.

Despite the fact that I am still processing my college experience, one of the things I have gathered is that while working as a curatorial intern, engaging with vanessa german’s THE RAREST BLACK WOMEN ON THE PLANET EARTH exhibit was one of the most rewarding experiences I had. german makes assemblage pieces using found materials that she gathers and collects. She takes beautiful pieces and listens to how they can contribute to a whole piece. One of my favorites, and the one the Mount Holyoke College community gathered to vote for the museum to acquire, was SKINNER & THE WASHERWOMAN IN THE GARDEN OF EDEN (2022). Seeing Black alums visit the exhibit at the alum conference, giving tours to community members, and hearing student guides research the pieces I couldn’t help but think about how to make a world outside of college an Eden on Earth for me as a Black woman.

A foundational text to my thesis on how Black Womxn can live artful lives in a heavily surveillance world was Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives: Beautiful Experiments Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. The most relevant definition of waywardness to my project of assemblage is described as:

“Wayward: the unregulated movement of drifting and wandering sojourns without a fixed destination, ambulatory possibility, interminable migrations, rush and flight, black locomotion; the everyday struggle to live free” (Hartman 2019, 227).

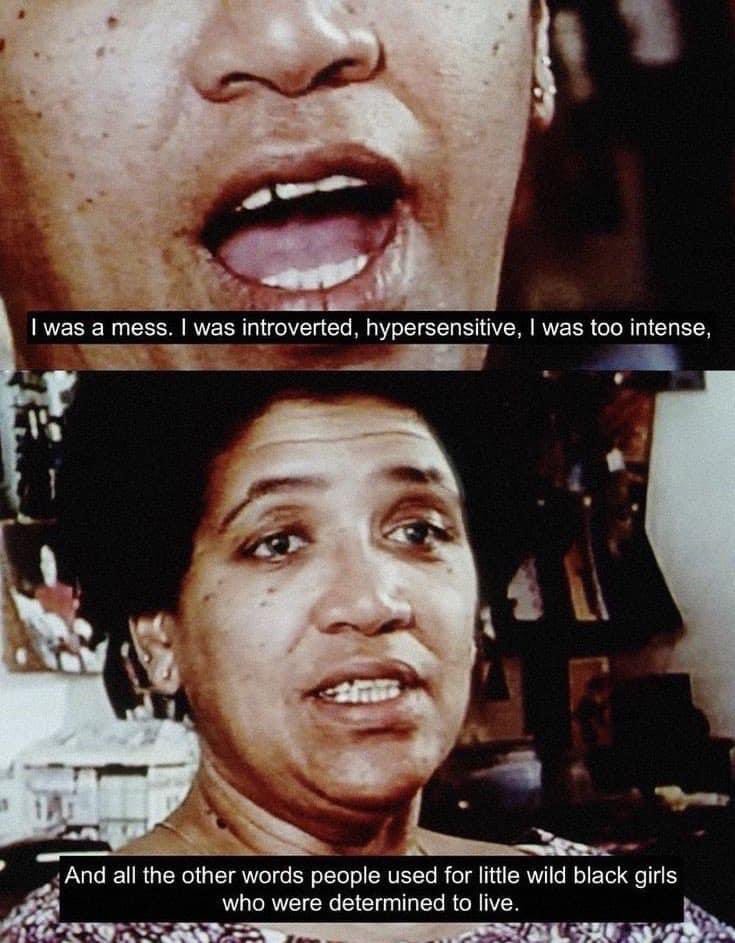

While all the characters moved me in different ways the story of Mattie Nelson has stayed with me the longest. Mattie craved to be in a state that ”transformed her into anything else she longed to be: like a bird flying high or a thing vast and boundless, ocean–not a person at all” (Hartman 2019,63). While normally, it is a proper standard to reference someone by their last name after initially mentioning their full name I can’t do that with Mattie. I seldom refer to Mattie as simply Nelson because her story resonates so deeply with my own. Mattie is a friend, a resonating echo of my own soul, kin that tells me tales of how they made every attempt to be triumphant in life, she is a mirror to things that I did not even know existed within me. Like Mattie, I too have a desire to find and if necessary take the life I want to live into my own hands; other people’s opinions be damned. Mattie made the intuitive decision that “if she didn’t decide how she wanted to live, then the world would dictate, and it would always cosign her to the bottom. Refusing this, “Mattie carried on as if she were free, and in the eyes of the world that was no different from acting wild” (Hartman 2019, 65). Growing up, I was often referred to by older Black womxn family members has wild or having a nasty attitude simply for demanding to be seen and heard. I talked back frequently, asked lots of questions until I got an answer I was satisfied with, & never took any disrespect (even from elders). This label of being wild is something else that makes me feel close to Mattie.

Mattie’s insistence on moving freely through the world also meant that she instinctively found beautiful things and claimed them as her own. Without second-guessing, or caring about the opinions of others, Mattie found and gathered beauty even if others labeled it stealing.

Hartman notes how “once she came home wearing a gold, bracelet, which belonged to a woman whose clothes she laundered. When her mother asked about it, she said she found it. Another time, she came home from work draped in a cashmere sweater that was the favorite sweater of her employer’s daughter. The next day she returned to work wearing it. As with Aurelia’s undergarments she made no attempt to hide these items” (Hatman 2019, 71). Her employer didn’t accuse “Mattie of stealing because she didn’t hide the items but wore them openly” (Hartman 2019, 71).

On another occasion, “Mattie found a locket and chain belonging to one of the children and placed it around her neck, she wore it in plain view, as if indifferent to rightful ownership and innocent of the notion of theft” (Hartman 2019, 71). Mattie had a desire to give and share as she pleased in a world set out to take away anything but the bare necessities from her. However, Mattie was determined to have both her bread and roses in her lifetime. As a result of Mattie’s defiant standard of her life she was well aware and took pride in the fact that “beautiful objects solicited her and she yielded to them, not caring about who owed them, not believing she had stolen anything” (Hartman 2019, 71). Mattie’s story is essential to understanding the definition of assemblage, as used in the context and the basis of this publication, as an ancient tool that Black womxn have used to claim subjectivity. Assemblage is an ancient way of defining a subject that is rooted in the vernacular of finding, gathering, and sharing in a community that knows beauty is essential to crafting an artful (& bountiful) life. Traditionally, according to Merriam Webster Dictionary, Assemblage is defined as a noun (see below).

Assemblage (noun)

1: a collection of persons or things : GATHERING

2: the act of assembling : the state of being assembled

3 a: an artistic composition made from scraps, junk, and odds and ends (as of paper, cloth, wood, stone, or metal)

b: the art of making assemblages

However, in the context of my thesis and this publication assemblage can be used as both a noun and a verb. Assemblage is a form of ancient conjuring for what it means for a Black womxn to present the whole soul unabashedly. Assemblage is the collection of things that Black womxn carry with them not just from point A to point B but anywhere they may choose to go. With the end goal of creating an artful life from those things that illicit an internal sense of beauty. Assemblage is rooted in the vernacular practice of gathering things around oneself; from the outskirts of where the world has placed Black womxn and making those things into conjuring instruments of freedom. The collected things then become magnetized for the Black womxn to use to create the theory of their own life. And like all theories, it is initiated using the portal that is the Black womxn’s body.

The process of making or partaking in assemblage is an art form. It is a way for Black womxn to create an artful life for themselves by any means necessary. Regardless of if the way Black womxn choose to assemble gathered things offends the codes of conduct placed upon them. Assemblage is not confined to a static or fixed location. Assemblage is a mobile modular technology of subjectivity that is in a state of constant flux. It is done in the open and made knowable to only those who do not need a translation, footnote, or analysis. If people look at the art Black womxn have made of their lives and only see a collection of trash, scraps, and junk then it is not their job to convince them of something different.

Assemblage is not fugitivity because beauty belongs to no one singular person. One can not be a fugitive if the system one is choosing to subvert was never about justice, to begin with. Assemblage is done in the open, like the Black enslaved womxn in South Carolina’s Lowcountry “who threw rice into the air to separate the husks from the kernels, part of the intricate work of processing rice, they used their skirts as nets to catch some of the wayward rice as it fell back down into the baskets” (Tiya Miles, All That She Carried, 2021, 208). As well as the fact that assemblage is done in spite of risk of not self-disciplining. In spite of it all, Black womxn make assemblages from their lives using fabrics, paychecks, and homemade brooms because they deserve it. Black womxn deserve to dwell in clean spaces, adorn their bodies beyond what was once called negro cloth, and create community by turning discarded food into masterpieces. Nothing discarded is trash because even the earth reuses soiled natural material. Assemblage is making every effort to have bread and blue roses in one’s everyday life. It is the only sustainable practice of self-love humans can partake in that does not destroy the ecosystem we live in. It is sharing clothesline, sugar, food, and trust. Trusting so that a 16-year-old child, Ralph Yarl, does not get shot in the head when trying to pick up his younger siblings.

Like the womxn of the convent in Toni Morrison’s Paradise, and nature itself, assemblage can not be controlled or manipulated into being whole in select spaces. Additionally, assemblage is not concerned with appearing or performing being an enigma of openness. Black womxn who make assemblages of their lives do not wish to be remembered as pastel smiles but as vivid blue rosettes with thorns included. Just like catching grains of raining wayward rice, assemblage is rooted in the land because anything else is manipulated to control. Assemblage is giving in to the desire to rest deeper, walk light, and work with the earth to create holistic communities not secured by barriers but nets. These nets can be used for the purpose of pooling and collecting resources to share with others well before Black womxn are surveilled. Nets can support Black Womxn before being murdered while forgetting to turn on a turning signal or murdered in a drug investigation while sleeping. Assemblage forges a new meaning of security not rooted in Western ideas of separation & borders.