Skinner Green was a space that many students traversed to get to points of campus quickly. In this case, Skinner Green was a nucleus of increased human foot traffic. This was evident in the dips of the land & the barren patches where grass was eroded by repetitive treks. However, at the start of the school year & near the end, Skinner Green was also a hub of leisure. Every afternoon students frolicked to the green to lay out their blankets & soak up the sun. Friends made patchwork quilts of their blankets on the lumpy green to ensure everyone had ample space. Folks shared snacks, played music, chatted, read books, tanned, & simply rested. During peak class courses the green served as a town square for folks to arrive at their classrooms of productivity faster. From the mid-day to afternoon it became a site to be still & gather. At least for a specific percentage of the student body that is.

For many folks, myself included, the green continued being sunken ground for us to cut across. Instead of heading to classrooms of productivity, we headed to our productive jobs. As we continued to slowly erode the grass, prohibiting it from re-generating, what I now know is we slowly eroded the ability to tend to ourselves. The ability to acknowledge & honor my body’s needs became compromised in exchange for tending to everything but myself. At any given time I was working a minimum of three jobs to support myself. Therefore, as each day passed I cut through the green racing to my next obligation with envy. I was especially envious when the weather was pleasantly beautiful. I longed to find an old blanket & rest for a while on soft cushions of support. However, a picnic blanket was not going to support me financially. It seemed that the green was a space for everyone to indulge & gather but me.

It wasn’t just this laborious experience, walking to work when I desired to lay in the sun, that communicated this to me. When I think of picnics my visuals stretch across many historical periods. The following picnics & information, at this point, are embodied from many interesting classes from my time at college. Those experiences have served as stepping stones for this stream of consciousness to emerge. The first picnic to appear in my mind is the central panel of Claude Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass 1865-66.

The artist’s hand is evident throughout the piece, especially in the borders between the light & shadow, despite the French Academy’s preference for perfect realism. In this painting, we see the four central figures, two sitting & two standing, in a heavily shaded area (no doubt because of the immense presence of trees). The objects we generally associate with a picnic are seen here: a picnic blanket centrally highlighted by white light, food & drink with plates for sharing, & green nature in which folks are nestled. The gaze of the sitting bearded figure & the sitting figure reaching for a plate seems to wander to the far right (a panel we are not privy to seeing). While the standing figures seem to be more intimately involved in a moment or conversation. None of these people looked like me. There are choices of which the people in this painting can decide how to spend their time at the picnic.

These same choices are present in Georges Seurant’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.

Utilizing, what was considered a renowned mastery of color theory, Seurant’s picnic scene has numerous activities taking place. We once again see the generous presence of trees offering a cool resting place. We see someone gathering flowers, smoking a pipe, a child running, & people sitting & walking. A new addition to this picnic scene is the presence of water. The addition of water provides another surface for even more activities for people to choose from. In Seuraunt’s piece, we see rowing & sailing as two new activities that emerge. As well as the meditative & respiratory systems aiding the choice of bearing witness to the water. During the 18th century, due to the Industrial Revolution, the Petit Bourgeoisie was created & on the rise. As a result, the people could experience & afford to have much more leisurely time in their lives. Once again, none of these people looked like me. There seems to be no interaction or excess amount of noise in the painting.

Then my mind swings to The Harvesters, sometimes referred to as The People’s Picnic, by Pieter Bruegel the Elder created in 1565.

This painting is considered by some to be the first modern landscape. Within “The People’s Picnic” we see a very different landscape rolled out before us. Whereas the trees fan out to provide cover for their subjects, in the two previous picnic scenes, none of that occurs here. Within this picnic, the trees are few and far between. The central tree people are gathered beneath, like the ones surrounding it, lack full foliage. Instead, these windy trees let the sun trespass through thin branches to continue burdening the laborers. While the painting most likely is based in Europe I always look to the trees. According to a 2021 study, cited in NPR’s Bringing Back Trees To 'Forest City's' Redlined Areas Helps Residents And The Climate article, research has shown that low-income areas with marginalized people lack significant tree coverage. Thus resulting in inequitable access to shade, cooling temperatures, & who deserves to be comfortable outside the privacy of their homes. In The Harvesters, there is just a small white blanket (or sheet) for people to gather around under the sparse tree. However the blanket, like the trees, does not extend enough for everyone to rest upon it. Since the sun shows no mercy the subjects don wide-brimmed sun hats while eating a modest meal. There are no pastries or wine present in Bruegel’s painting.

Furthermore, while in the other two picnic scenes, people are given ample choices of activities only two are present here. The people sitting & eating will return to the golden maze to harvest. The second activity is that the people in the golden maze will pause for a blistering respite. The third unpictured truth is that this cycle will continue to repeat itself. The subjects actively harvesting, engaged in literal back-bending labor, will straighten their spine only to hear it buckle once again as a result of labor. While I relate to these subjects’ positions as laborers none of them look like me. As such, my brain swings to a literal swing.

The Swing was painted in 1767 by Jean-Honoré Fragonard during the every indulgent Rocco period. The French elite was consumed with the wonders & privileges that came with being a part of the elite class. While there is no picnic present here the attitude of the second definition is present here.

“A pleasant or amazingly carefree experience.”

The swing is thought of by many as a leisurely activity in the same way that a picnic is. While this painting was leisurely & pleasurable, it was commissioned by a man to forever memorialize his love, it’s also an activity that subjects choose to release the strict social restrictions on one’s body. The swing is a playful activity with one’s kicking legs, clothes billowing, & giddy laughter cutting through the shadowy landscape. A revered landscape that thus far in this picnic promenade is strictly European.

The image my mind conjures when I try to place picnic scenes within the context of the United States is one I continuously shiver at the thought of seeing. The popular picnics of the United States social scene are ones I would not have actively participated in. These picnics reek of terror & poplar trees dropping a strange & bitter crop. While the word picic was not popularized or originated within the violence of Jim Crow, it was a term that was used to organize & normalize the active participation & witnessing of infusing terror into the daily lives of Black people. The United States picnic is one where white people come together around a burning Black person’s body—mushroomed carbon smoke particles (imagery from Marielle, Presente!)—& happily ate & drank. So where do I, a Southern Black Woman fit into these two disturbing isolated ideals of picnics whole & revered, of the land, & ahead of my time? The swing tethers & at once frees you—catapults you into flight. As my mind continues kicking, from racing to flying I find her—someone who takes up space in this patchwork landscape who resembles me.

Not only does Fly tether & free you but reminds us of the often truncated space between childhood & adulthood for Black children. Adrienne’s work tethers us to the reality that Black children deserve to be children just as long as other kids. Black children deserve to experience their full childhood & make mistakes uninterrupted by public opinions of the moment they become “grown.” Perhaps this is illustrated in the shadowed tree on the ground we see creeping beneath the subject. Or perhaps the tree present only in shadow is a symbol of support, shade, & safety from whatever people closer to the white building in the distance may be saying. Perhaps, this swing tethered to a shadowed tree serves as a reminder that there is refuge in darkness. You don’t have to face blinding enlightenment & expansion & colonization obscured as curiosity alone. There’s always an anchored tree to come back to & play beneath.

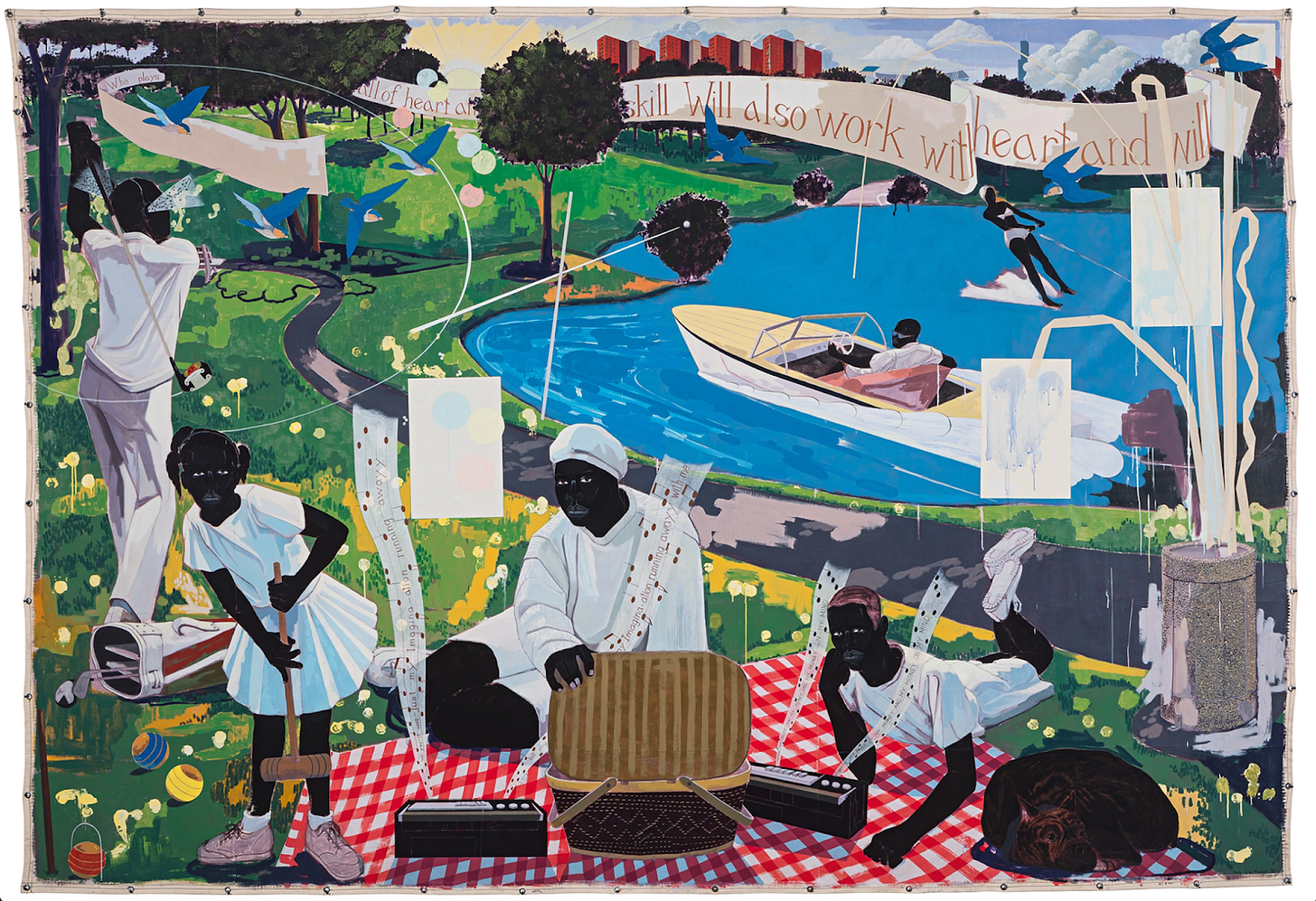

This same anchor soothes us in Past Times by Kerry James Marshall.

In this picnic scene, there are Black people-centered & present. There is a child playing croquet, a subject golfing, a subject on a boat, a subject water skiing, & all subjects listening to music wafting through the air. Whereas Seurant’s picnic appeared to be static & devoid of interaction, Kerry gives us insight into the sounds that permeate the landscape of Past Times. The first stereo, in front of the central figure on the checkered picnic blanket & to the left of the basket, has floating music notes coming out of it. The music notes read

“it was just my imagination running away.”

This line is from the 1971 Temptations song entitled Just My Imagination (Running Away With Me).

In contrast, the second stereo directly in front of the figure to the right of the basket has music notes that read

“my mind on my money & my money on my mind.”

This is a popular line that is referenced in many contemporary songs. However, because this painting was created in 1997, I would most likely attribute this reference to the 1994 song Gin & Juice by Snoop Dog.

Maybe these two stereos & different song choices allude to a generational difference between the two seated subjects. However, these two stereos could also ricochet off each other to underscore the tension of achieving the picturesque American Dream that so many folks hold in their imaginations. Additionally, for me, these two song lyric excerpts communicate that the dream is still heavily reliant on capitalism. My Mind on my money, money on my mind. Although this painting does center Black folk in a scene of leisure representation will not save us (see clip from Dr. Ruha Benjamin’s 2024 Spellmen Convocation Speech). Neither will simply placing Black folk in images that harken to European visuals of success marking & making. Therefore, I offer the following fractural critique of Past Times as a new lens to approach the work.

Karey placing a banner across this green space that reads “will also work with heart and will…” provides a legibility that does not need to be stated. The history of the United States, our grandmothers cleaning houses, our aunts opening hair salons, our family members working multiple jobs, our cousins organizing as activists, our mothers finding a way to ensure our every need was met, 400 years of slavery, we don’t need to remind of our valuable “marketable” skills. We certainly do not need a marketable reminder when Black folks are at rest or participating in leisurely activities. The documentation of Black folk resting does not have to be accompanied by an asterisked reminder to the systems that exploit us that we are still ripe for the picking as we play.

I think the better banner is the less legible one surrounded by circling blue birds on the left side of the painting that simply reads who plays. If this banner is one continuous message blocked by trees to read who plays all of heart and skill will also work with heart and will… then my sentiment remains the same. This full sentence could be seen as an argument to increase access to green spaces & trees for working-class Black folk. This is a possibility that I present to you. However, providing access to leisure, green spaces, clean air, etc. should not be done in the hopes that the reward will be more productive workers who will continue to produce profit. Access to green spaces should be a given because it’s a human right. We don’t need the looming city/workspace in the background to serve as a model of having the best of both worlds. I desire a new world where my leisure isn’t earned but a given. I desire a new world where our identities aren’t related to an easily digestible job and where we see how much we can produce. Let’s ask who plays & let the disparities rip apart the very fabric of the picnic blanket we call society. We have tried to imagine this blanket being large enough for all of us, as shown through my picnic analysis promenade, but have failed each time. What if the grass, we try so hard to cover up from fear of being uncomfortable, is the largest most accessible blanket we can gather upon to welcome us home?

Black Edens

Everything has been touched by the same sun. Therefore, as I incanted the desire for the world I envisioned above to break through, I am already reaching back to pull on the moments the question who plays was answered by generations before me. These folk knew the grass & sand was a blanket large enough for families to gather upon. These folk knew access to leisure & green spaces did not come after proof of exhaustive labor. These unruly wayward folk knew the value of the land was not related to what you could extract from it.

A touching example of these folk is the Reels Family. Within the documentary Silver Dollar Road (released on October 13th, 2023 & directed by Raul Peck), the Reels family fights to protect, preserve, & honor the waterfront property that been passed down in their family since the first generation after chattel slavery ended. We see the Reels family, rooted in North Carolina face threats of losing their land & freedom by land developers wanting a valuable piece of waterfront property. This land was once discarded, on the periphery, & tended to by Black folk who made it a playground for loved ones to wonder & wander. Similarly to how I look to the trees, I also look to the water to spot whose footprints were intentionally washed away. Mamie Ellison, the daughter of the Matriarch (Gertrude) of the family, is leading the charge to ensure the family land stays in the family. Mamie recalls her flooded memory of growing up on Silver Dollar Road.

“When I was a little girl and growing up here on Silver Dollar Road, I like thinking about those days cause it was so innocent. It was magical. You just felt free, you felt happy, and you felt love. It was like a village, you know. You was free to roam and play, and you had the water. And going to the water, for me, was magical.” — [3:46-4:18]

Going down to the water is a magical experience. Especially for folks across the African Diaspora who live or frequent near the Atlantic Ocean. Having direct access to the water via the family’s private beach was magical for Mamie & for her niece Kim Duhon (granddaughter of Gertude) it was also a liberating experience.

“I lived in New Orleans, and we would come down every summer. And it was almost like two weeks before we knew it was time to go back to New Orleans, the depression would sit in. Oh, we’d cry cause we didn’t want that Friday to come when Mom and Dad was coming to get us. It was just the nostalgia of just having that freedom. We walked around in our bare feet from this aunt’s house to that aunt’s house to cousins’ houses. And, “Can you take us swimming today? Cause Grandma said we can’t go down unless we have an adult.” We had our own beach. My Uncles would bring their boats to the pier, and we’d run up, help them offload shrimp and fish and crabs. And it was a good time—music, dancing, barbecues, concerts or local churches just putting on gospel concerts and baptisms in the water. Being in the sun, the sand, being stung by sting rays and running out. And putting sand on you, just trying to get the stinging off. It was just amazing. I did go to the market with Grandma to help out. Grandma was very well respected. And she had a lot of clientele when it came down to the produce and the seafood that she sold. Technically, she was probably considered one of the richest Black women in the community because their property… was so, um, valuable. And not valuable to us from a monetary stand point, but valuable to us because of the history, you know, and the beauty of it.” — [4:48-6:38]

While the fight to retain generational land continues there are also sites of memory created specifically for Black people to vacation. These sites were especially important during legalized segregation when leisure spaces were also separate and unequal. Many descendants of Black families who established resort communities, one of the most referenced ones lovingly called Black Eden, are fighting for their sites as well.

This is the historical research, archival analysis, & storytelling that the breath taking House of Aama’s Salt Water SS22 collection is rooted within. House of Aama too is reaching back to start a discourse around the question who plays. On the House of Aama website, the mother-daughter-run company introduces the collection through a video teaser. The video trailer caption can be read below.

“Welcome to Camp Aama! Through this abstract short we reimagine resort life through the lens of emerging fashion design label, House of Aama. Camp Aama, a vision of an exclusively Black resort in upstate NY is a safe place for Black families to exist and experience unadulterated joy with one another. This spiritually guarded resort can only be accessed through a coded drawing or an offering which then transports you beyond the trees and to the resort grounds. Throughout the short film our narrator introduces us to the mystique and joyful happenings at this resort while we watch vignettes of the resort goers enjoy each other and the land.”

While I have yet to experience a physical Black Eden resort space I have come to know the feeling. We unruly folk know that when accessing the physical Black Eden proves to be difficult there are a multitude of ways to access it within.

Our Black Eden is our breath

Our Black Eden is opening my window while at work

Our Black Eden is convincing professors to have class outside so I can enjoy the day

Our Black Eden is running through sprinklers & fire hydrants

Our Black Eden is waking up a little earlier or staying up a little later for time for ourselves

Our Black Eden is resting our eyes

Our Black Eden is sitting on the porch

Our Black Eden is wherever we gather

Please remember if you choose to quote this piece, share this piece, or any piece on this publication to always CITE BLACK WOMEN. Please always include my name (Kay Brown she/her pronouns) and a link to the publication of the Assemblage: Baby’s Breath substack in your sharing practice.

To further support my writing practice, receive additional offerings that connect to my pieces, & be the first to hear about other ways to engage in the theory of Assemblage, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Soon I will invite fellow unruly folks to practice gathering & honoring with me in a generous clearing ✨. Stay tuned for updates!

Lastly, remember, that referrals are now available! This means you get to speak the name Assemblage: Baby’s Breath out loud to your community while receiving unique grounded gathered gifts from me. Thank you for being here 💙.

Ive been pondering about what rituals of rest and joy I have and where I have been starving myself of such pleasure. Going through this thoughtful deep dive and landing on Black Eden was just what I needed 🤍

Yes! I love being the first or last one awake for the peace. It truly is Eden.